Optimizing SQL CASE Expression Evaluation

Posted on: Mon 02 February 2026 by Pepijn Van Eeckhoudt

SQL's CASE expression is one of the few explicit conditional evaluation constructs the language provides.

It allows you to control which expression from a set of expressions is evaluated for each row based on arbitrary boolean expressions.

Its deceptively simple syntax hides significant implementation complexity.

Over the past few Apache DataFusion releases, a series of improvements to CASE expression evaluator have been merged that reduce both CPU time and memory allocations.

This post provides an overview of the original implementation, its performance bottlenecks, and the steps taken to address them.

Background: CASE Expression Evaluation¶

SQL supports two forms of CASE expressions:

- Simple:

CASE expr WHEN value1 THEN result1 WHEN value2 THEN result2 ... END - Searched:

CASE WHEN condition1 THEN result1 WHEN condition2 THEN result2 ... END

The simple form evaluates an expression once for each input row and then tests that value against the expressions (typically constants) in each WHEN clause using equality comparisons.

Here's an example of the simple form:

CASE status

WHEN 'pending' THEN 1

WHEN 'active' THEN 2

WHEN 'complete' THEN 3

ELSE 0

END

In this CASE expression, status is evaluated once per row, and then its value is tested for equality with the values 'pending', 'active', and 'complete' in that order.

The CASE expression evaluates to the value of the THEN expression corresponding to the first matching WHEN expression.

The searched CASE form is a more flexible variant.

It evaluates completely independent boolean expressions for each branch.

This allows you to test different columns with different operators per branch as shown in the following example:

CASE

WHEN age > 65 THEN 'senior'

WHEN childCount != 0 THEN 'parent'

WHEN age < 21 THEN 'minor'

ELSE 'adult'

END

In both forms, branches are evaluated sequentially with short-circuit semantics: for each row, once a WHEN condition matches, the corresponding THEN expression is evaluated.

Any further branches are not evaluated for that row.

This lazy evaluation model is critical for correctness.

It lets you safely write CASE expressions like CASE WHEN d != 0 THEN n / d ELSE NULL END that are guaranteed to not trigger divide-by-zero errors.

Besides CASE, there are a few conditional scalar functions that provide similar, more restricted capabilities.

These include COALESCE, IFNULL, and NVL2.

You can consider each of these functions as the equivalent of a macro for CASE.

For example, COALESCE(expr1, expr2, expr3) expands to:

CASE

WHEN expr1 IS NOT NULL THEN expr1

WHEN expr2 IS NOT NULL THEN expr2

ELSE expr3

END

Since Apache DataFusion rewrites these conditional functions to their equivalent CASE expression, any optimizations related to CASE described in this post also apply to conditional function evaluation.

CASE Evaluation in DataFusion 50.0.0¶

For the remainder of this post, we'll be looking at 'searched CASE' evaluation. 'Simple CASE' uses a distinct, but very similar implementation. The same set of improvements has been applied to both.

The baseline implementation in DataFusion 50.0.0 evaluated CASE using a common, straightforward approach:

- Start with an output array

outwith the same length as the input batch, filled with nulls. Additionally, create a bit vectorremainderwith the same length and each value set totrue. - For each

WHEN/THENbranch:- Evaluate the

WHENcondition for the remaining unmatched rows usingPhysicalExpr::evaluate_selection, passing in the input batch and theremaindermask. - If any rows matched, evaluate the

THENexpression for those rows usingPhysicalExpr::evaluate_selection. - Merge the results into the

outarray using thezipkernel. - Update the

remaindermask to exclude the matched rows.

- Evaluate the

- If there's an

ELSEclause, evaluate it for any remaining unmatched rows and merge usingzip.

Here's a simplified version of the Rust code for the original loop:

let mut out = new_null_array(&return_type, batch.num_rows());

let mut remainder = BooleanArray::from(vec![true; batch.num_rows()]);

for (when_expr, then_expr) in &self.when_then_expr {

// Determine for which remaining rows the WHEN condition matches

let when = when_expr.evaluate_selection(batch, &remainder)?

.into_array(batch.num_rows())?;

// Ensure any `NULL` values are treated as false

let when_and_rem = and(&when, &remainder)?;

if when_and_rem.true_count() == 0 {

continue;

}

// Evaluate the THEN expression for matching rows

let then = then_expr.evaluate_selection(batch, &when_and_rem)?;

// Merge results into output array

out = zip(&when_and_rem, &then_value, &out)?;

// Update remainder mask to exclude matched rows

remainder = and_not(&remainder, &when_and_rem)?;

}

Let's examine one iteration of this loop for the following CASE expression:

CASE

WHEN col = 'b' THEN 100

ELSE 200

END

Schematically, it will look as follows:

This implementation works perfectly fine, but there's significant room for optimization, mostly related to the usage of evaluate_selection.

To understand why, we need to dig a little deeper into the implementation of that function.

Here's a simplified version of it that captures the relevant parts:

pub trait PhysicalExpr {

fn evaluate_selection(

&self,

batch: &RecordBatch,

selection: &BooleanArray,

) -> Result<ColumnarValue> {

// Reduce record batch to only include rows that match selection

let filtered_batch = filter_record_batch(batch, selection)?;

// Perform regular evaluation on filtered batch

let filtered_result = self.evaluate(&filtered_batch)?;

// Expand result array to match original batch length

scatter(selection, filtered_result)

}

}

Going back to the same example as before, the data flow in evaluate_selection looks like this:

The evaluate_selection method first filters the input batch to only include rows that match the selection mask.

It then calls the regular evaluate method using the filtered batch as input.

Finally, to return a result array with the same number of rows as batch, the scatter function is called.

This function produces a new array padded with null values for any rows that didn't match the selection mask.

So how can we improve the performance of the simple evaluation strategy and use of evaluate_selection?

Opportunity 1: Early Exit¶

The CASE evaluation loop always iterates through all branches, even when every row has already been matched.

In queries where early branches match all rows, this results in unnecessary work being done for the remaining branches.

Opportunity 2: Optimize Repeated Filtering, Scattering, and Merging¶

Each iteration performs a number of operations that are very well-optimized, but still take up a significant amount of CPU time:

- Filtering:

PhysicalExpr::evaluate_selectionfilters the entireRecordBatchfor each branch. For theWHENexpression, this is done even if the selection mask was entirely empty. - Scattering:

PhysicalExpr::evaluate_selectionscatters the filtered result back to the originalRecordBatchlength. - Merging: The

zipkernel is called once per branch to merge partial results into the output array

Each of these operations needs to allocate memory for new arrays and shuffle quite a bit of data around.

Opportunity 3: Filter only Necessary Columns¶

The PhysicalExpr::evaluate_selection method filters the entire record batch, including columns that the current branch's WHEN and THEN expressions don't reference.

For wide tables (many columns) with narrow expressions (few column references), this is wasteful.

Suppose you have a table with 26 columns named a through z, and the following simple CASE expression:

CASE

WHEN a > 1000 THEN 'large'

WHEN a >= 0 THEN 'positive'

ELSE 'negative'

END

The implementation would filter all 26 columns even though only a single column is needed for the entire CASE expression evaluation.

Again this involves a non-negligible amount of allocation and data copying.

Performance Optimizations¶

Optimization 1: Short-Circuit Early Exit¶

The first optimization is straightforward. As soon as we detect that all rows of the batch have been matched, we break out of the evaluation loop:

let mut remainder_count = batch.num_rows();

for (when_expr, then_expr) in &self.when_then_expr {

if remainder_count == 0 {

break; // All rows matched, exit early

}

// ... evaluate branch ...

let when_match_count = when_value.true_count();

remainder_count -= when_match_count;

}

Additionally, we avoid evaluating the ELSE clause when no rows remain:

if let Some(else_expr) = &self.else_expr {

remainder = or(&base_nulls, &remainder)?;

if remainder.true_count() > 0 {

// ... evaluate else ...

}

}

For queries where early branches match all rows, this eliminates unnecessary branch evaluations and ELSE clause processing.

This optimization was implemented by Pepijn Van Eeckhoudt (@pepijnve) in PR #17898

Optimization 2: Optimized Result Merging¶

The second optimization fundamentally restructures how the results of each loop iteration will be merged.

The diagram below illustrates the optimized data flow when evaluating the CASE WHEN col = 'b' THEN 100 ELSE 200 END from before:

In the reworked implementation, the evaluate_selection function is no longer used.

The key insight is that we can defer all merging until the end of the evaluation loop by tracking result provenance.

This was implemented with the following changes:

- Augment the input batch with a column containing row indices.

- Reduce the augmented batch after each loop iteration to only contain the remaining rows.

- Use the row index column to track which partial result array contains the value for each row.

- Perform a single merge operation at the end instead of a

zipoperation after each loop iteration.

These changes make it unnecessary to scatter and zip results in each loop iteration.

Instead, when all rows have been matched, we then merge the partial results using arrow_select::merge::merge_n.

The diagram below illustrates how merge_n works for an example where three WHEN/THEN branches produced results.

The first branch produced the result A for row 2, the second produced B for row 1, and the third produced C and D for rows 4 and 5.

The merge_n algorithm scans through the indices array.

For each non-empty cell, it takes one value from the corresponding values array.

In the example above, we first encounter 1.

This takes the first element from the values array with index 1, resulting in B.

The next cell contains 0 which takes A, from the first array.

Finally, we encounter 2 twice.

This takes the first and second element from the last values array respectively.

This algorithm was initially implemented in DataFusion for the CASE implementation, but in the meantime has been generalized and moved into the arrow-rs crate as arrow_select::merge::merge_n.

This optimization was implemented by Pepijn Van Eeckhoudt (@pepijnve) in PR #18152

Optimization 3: Column Projection¶

The third optimization addresses the "filtering unused columns" overhead through projection.

Look at the following query example where the mailing_address table has the columns name, surname, street, number, city, state, country:

SELECT *, CASE WHEN country = 'USA' THEN state ELSE country END AS region

FROM mailing_address

You can see that the CASE expression only references the columns country and state, but because all columns are being queried, projection pushdown cannot reduce the number of columns being fed in to the projection operator.

During CASE evaluation, the batch must be filtered using the WHEN expression to evaluate the THEN expression values.

As the diagram above shows, this filtering creates a reduced copy of all columns.

This unnecessary copying can be avoided by first narrowing the batch to only include the columns that are actually needed.

At first glance, this might not seem beneficial, since we're introducing an additional processing step. Luckily projection of a record batch only requires a shallow copy of the record batch. The column arrays themselves are not copied, and the only work that is actually done is incrementing the reference counts of the columns.

Impact: For wide tables with narrow CASE expressions, this dramatically reduces filtering overhead by removing the copying of unused columns.

This optimization was implemented by Pepijn Van Eeckhoudt (@pepijnve) in PR #18329

Optimization 4: Eliminating Scatter in Two-Branch Case¶

Some of the earlier examples in this post use expressions of the form CASE WHEN condition THEN expr1 ELSE expr2 END to explain how the general evaluation loop works.

For this kind of two-branch CASE expression, Apache DataFusion has a more optimized implementation that unrolls the loop.

This specialized ExpressionOrExpression fast path still used evaluate_selection() for both branches which uses scatter and zip to combine the results incurring the same performance overhead as the general implementation.

The revised implementation eliminates the use of evaluate_selection as follows:

// Compute the `WHEN` condition for the entire batch

let when_filter = create_filter(&when_value);

// Compute a compact array of `THEN` values for the matching rows

let then_batch = filter_record_batch(batch, &when_filter)?;

let then_value = then_expr.evaluate(&then_batch)?;

// Compute a compact array of `ELSE` values for the non-matching rows

let else_filter = create_filter(¬(&when_value)?);

let else_batch = filter_record_batch(batch, &else_filter)?;

let else_value = else_expr.evaluate(&else_batch)?;

This produces two compact arrays, one for the THEN values and one for the ELSE values, which are then merged with the merge function.

In contrast to zip, merge does not require both of its value inputs to have the same length.

Instead it requires that the sum of the length of the value inputs matches the length of the mask array.

This eliminates unnecessary scatter operations and memory allocations for one of the most common CASE expression patterns.

Just like merge_n, this operation has been moved into arrow-rs as arrow_select::merge::merge.

This optimization was implemented by Pepijn Van Eeckhoudt (@pepijnve) in PR #18444

Optimization 5: Table Lookup of Constants¶

Up until now, we've discussed the implementations for generic CASE expressions that use non-constant expressions for both WHEN and THEN.

Another common use of CASE is to perform a mapping from one set of constants to another.

For instance, you can expand numeric constants to human-readable strings using the following CASE example.

CASE status

WHEN 0 THEN 'idle'

WHEN 1 THEN 'running'

WHEN 2 THEN 'paused'

WHEN 3 THEN 'stopped'

ELSE 'unknown'

END

A final CASE optimization recognizes this pattern and compiles the CASE expression into a hash table.

Rather than evaluating the WHEN and THEN expressions, the input expression is evaluated once, and the result array is computed using a vectorized hash table lookup.

This approach avoids the need to filter the input batch and combine partial results entirely.

The result array is computed in a single pass over the input values, and the computation time does not grow significantly with the number of WHEN branches in the CASE expression.

This optimization was implemented by Raz Luvaton (@rluvaton) in PR #18183

Results¶

The degree to which the performance optimizations described in this post will benefit your queries is highly dependent on both your data and your queries.

To give some idea of the impact, we ran the following query on the TPC_H orders table with a scale factor of 100:

SELECT

*,

case o_orderstatus

when 'O' then 'ordered'

when 'F' then 'filled'

when 'P' then 'pending'

else 'other'

end

from orders

This query was first run with DataFusion 50.0.0 to get a baseline measurement.

The same query was then run with each optimization applied in turn.

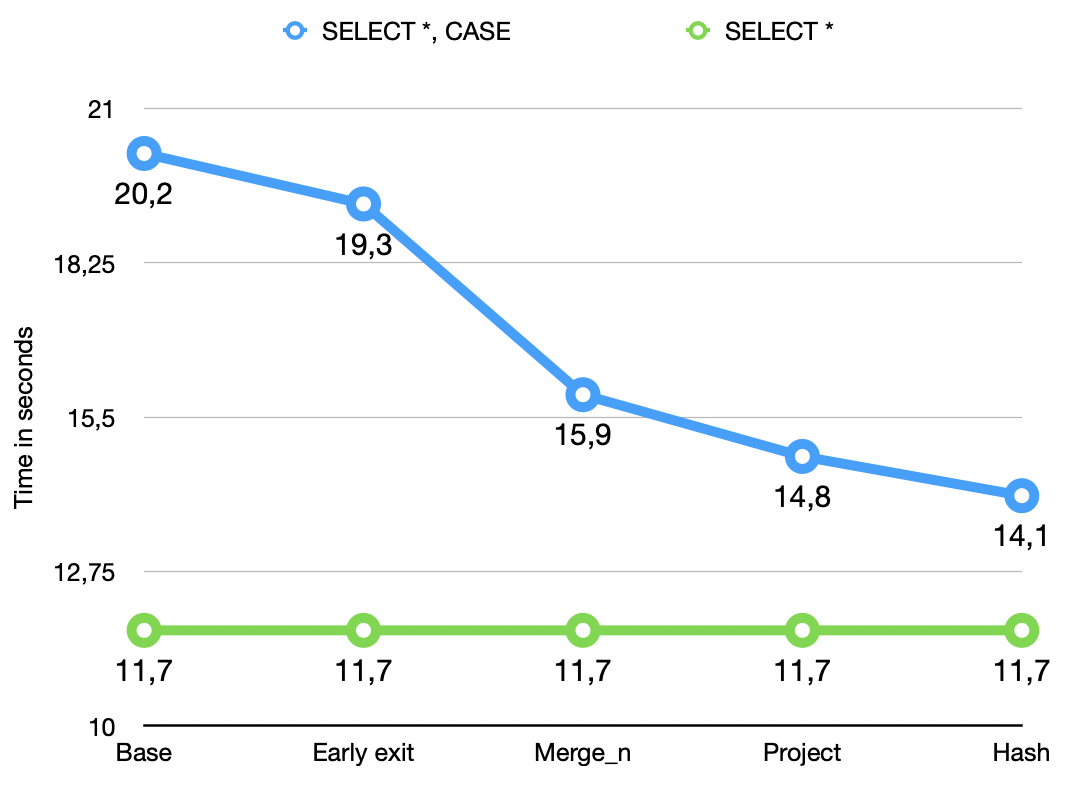

The recorded times are presented as the blue series in the chart below.

The green series shows the time measurement for the SELECT * FROM orders to give an idea of the cost the addition of a CASE expression in a query incurs.

All measurements were made with a target partition count of 1.

What you can see in the chart is that the effect of the various optimizations compounds up to the project measurement.

Up to that point these results are applicable to any CASE expression.

The final improvement in the hash measurement is only applicable to simple CASE expressions with constant WHEN and THEN expressions.

The cumulative effect of these optimizations is a 63-71% reduction in CPU time spent evaluating CASE expressions compared to the baseline.

Summary¶

Through a number of targeted optimizations, we've transformed CASE expression evaluation from a simple, but unoptimized implementation into a highly optimized one.

The optimizations described in this post compound: a CASE expression on a wide table with multiple branches and early matches benefits from all four optimizations simultaneously.

The result is significantly reduced CPU time and memory allocation in SQL constructs that are essential for ETL-like queries.

About DataFusion¶

Apache DataFusion is an extensible query engine, written in Rust, that uses Apache Arrow as its in-memory format. DataFusion is used by developers to create new, fast, data-centric systems such as databases, dataframe libraries, and machine learning and streaming applications. While DataFusion’s primary design goal is to accelerate the creation of other data-centric systems, it provides a reasonable experience directly out of the box as a dataframe library, Python library, and command-line SQL tool.

DataFusion's core thesis is that, as a community, together we can build much more advanced technology than any of us as individuals or companies could build alone. Without DataFusion, highly performant vectorized query engines would remain the domain of a few large companies and world-class research institutions. With DataFusion, we can all build on top of a shared foundation and focus on what makes our projects unique.

How to Get Involved¶

DataFusion is not a project built or driven by a single person, company, or foundation. Rather, our community of users and contributors works together to build a shared technology that none of us could have built alone.

If you are interested in joining us, we would love to have you. You can try out DataFusion on some of your own data and projects and let us know how it goes, contribute suggestions, documentation, bug reports, or a PR with documentation, tests, or code. A list of open issues suitable for beginners is here, and you can find out how to reach us on the communication doc.

Comments

We use Giscus for comments, powered by GitHub Discussions. To respect your privacy, Giscus and comments will load only if you click "Show Comments"